Every so often, a friend and I wish for more books in a category I sometimes call “’90s coffeeshop fantasy.” There are too few books in this category. “Something like Charles de Lint, but not” my friend will say. “Like Girl, but with magic,” I’ll suggest. “More books kind of like Pamela Dean’s Tam Lin,” we agree. But it’s a space that’s hard to pin down and define—elusive, magical, but like real life, too.

And then I read Michelle Ruiz Keil’s Summer in the City of Roses, which is all of this and so much more. Lush, empathetic, strident, puckish, infused with a street-level punk-rock magic, it’s the kind of fairy tale my teen self didn’t even know a person could dream of. Much of its magic hums along like a current beneath the book’s skin, bursting out in full bloom for a transformative finale. But it’s there all along, if you’re looking—and this is the kind of book you want to give your full attention to.

Iphigenia and Orestes—Iph and Orr—are Greek-Mexican-American siblings in the comfortable suburbs of Portland, Oregon, in the ‘90s. Iph has always protected sensitive Orr, who has a tough time with the world, but when their mother goes away for an artist’s residency (a choice that isn’t easy for her to make), their careful family balance falls apart. Their father sends Orr to a mountainside boot camp meant to toughen him up—a transformation only their father wants for Orr. He tells no one, and when Iph finds out, she lights out into the streets of Portland with no clear goal but a powerful anger.

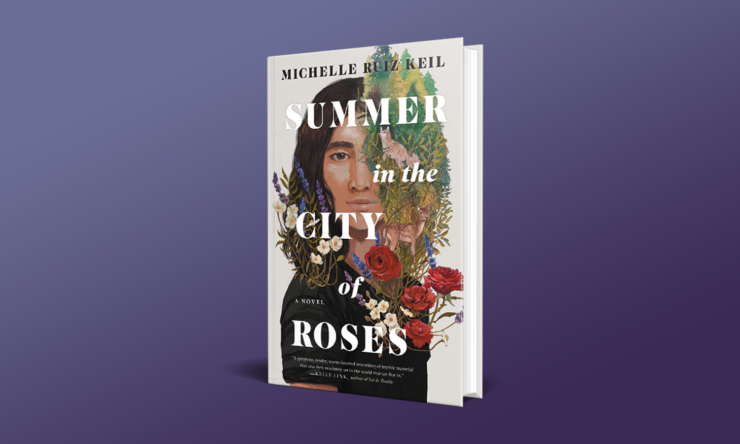

Buy the Book

Summer in the City of Roses

What she finds is not Orr but George, a bicycle-riding, bow-carrying, magical-pit-bull-owning rescuer with “a boy’s name, but not a boy’s voice.” (Keil cleverly avoids using pronouns for George, who likely wouldn’t have considered using “they/them” at the time the story is set, but might now.) George opens the door to a Portland that sheltered Iph has never seen—the one full of musicians and dancers and sex workers, all-ages venues and vintage stores and young people trying to make their own way in the world. Iph’s quest criss-crosses Portland’s bridges, takes her up into the wealthy hills and down into the depths of Old Town. George, in a very real way, shows her the world—the way the world can be at your feet and you don’t even know it.

But this story belongs to both Iph and Orr, whose escape from the boot camp comes with the help of the smallest of creatures. Stumbling down the mountain, he finds himself taken in by a riot grrl band called The Furies, who let him stay in their pink house and treat him with a gentle respect that does more than any boot camp could to show Orr what he’s capable of. The way Orr relates to the world is strange to most people, but his perspective is full of grace—and normal kid stuff, like Agent Scully and maps and running.

Though Iph and Orr take their full names from mythology, the short versions are equally powerful here: they’re both options, possibilities. If this. Or that. And when a story set in Portland has an Orr and a George, it’s impossible not to see at least a slight echo of Ursula K. Le Guin’s George Orr, who in The Lathe of Heaven dreamed new realities into being. This Orr isn’t changing the world on such a large scale, but his dreams are vivid, and his choices change things in subtle but monumental ways. They change his family; they change his relationship to Iph; and they change his understanding of who he is and how he should be in the world.

Summer in the City of Roses is a book full of details and emotions so precise that they can feel like something remembered instead of read. A girl and her crush’s ex find a way to connect. A boy can barely watch a movie due to the feeling of the girl sitting next to him. The air is full of crows and roses; there are snatches of Shakespeare and movies and songs and a truly magical vintage dress. Keil fills her book with lovingly drawn secondary characters: scrappy young musicians; the owner of a vintage shop; a struggling couple in a rundown hotel. They are wealthy, poor, loving, hurting, growing up or growing old, almost all queer and often brown-skinned. Portland is a very white city, but when people speak as if it’s entirely populated with white people, they erase whole populations and histories. Keil’s Portland looks a lot more like the real thing.

As in her debut novel, All of Us With Wings, Keil doesn’t shy away from the darker side of life, whether that’s addiction or generational trauma or assault. What she shows, with grace and care, is how pain never just affects one person, but radiates outward, like a bruise, fainter on the edges but still tender. Iph and Orr grew up comfortable, but their family isn’t without pain and heavy history, and part of what they learn, as they venture through their new worlds, is that everyone carries their own versions of those weights.

For much of the story, the magic of this book is the understated kind: the magic of finding the right people, the right places; the magic of taking the necessary steps to make connections, to be brave, to let go. But as the story draws to its close, it steps deeper into the woods, and the magic grows brighter, coming closer to the surface. These particular woods will be familiar to Portland readers, but you don’t have to know anything about this city to recognize the elements Keil draws on for her finale—both well-worn and well-loved tropes and a host of elements all her own. (At one point, Iph finds a list of books in a magical library that clearly relate directly to the story Keil is telling, and to thinking about fairy tales in general; this is absolute catnip for a reader like me.)

I read this book in two days during a Portland heat wave, sweating and miserable and wishing I could go walk the streets Iph and Orr wander, to go by the places that used to be all-ages venues, to visit a nearby tiny bookstore which seems like it might have emerged from that era. For me, there’s nostalgia in this story, but it’s more than that; it’s a reminder that all these little magics are still here, still everywhere, in the bonds of friends becoming family, people taking one another in, people connecting in ways that don’t fit the dominant narratives and are all the more powerful for it. The family that finds Orr, in the end, is not the same one who let him go. It’s bigger, it’s brighter, and it’s full of complicated love. Keil is a wise guide through these streets, and one that knows that while kids are smarter than they get credit for, they also need to be protected—but the form protection takes can vary.

This book is everything I could want in a ’90s coffeeshop fantasy: Clever and loving protagonists, a deep sense of place, a growing sense of belonging, a view of the world that centers those usually on the margins, fairy tales (specifically the Grimms’ “Brother and Sister,” but others, too) and myth all mashed together with poetry and performance and all kinds of love, heavy and bright at once. Between this and her gorgeous debut, All of Us With Wings, Keil is building her own fantastical world, a gritty and shining Northern California/Pacific Northwest like the fairy-tale punk-rock kids might dream of when they look north from Francesca Lia Block’s Los Angeles. It’s truly a wonder.

Summer in the City of Roses is available from Soho Teen.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. You can also find her on Twitter.